By Marilyn Bechtel

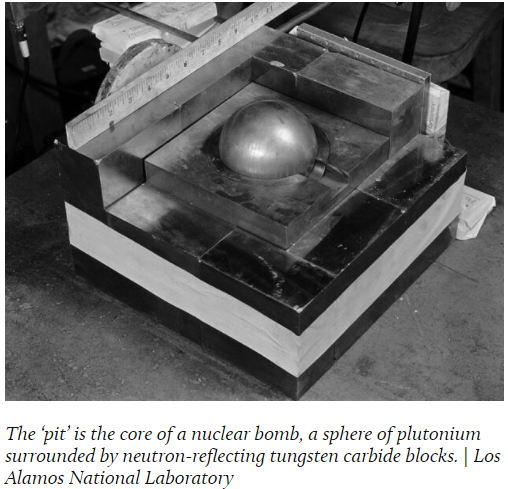

Four public interest groups monitoring the nation’s nuclear weapons development sites are demanding the Department of Energy and the National Nuclear Security Agency conduct a thorough environmental review of their plans to produce large quantities of a new type of nuclear bomb core, or plutonium pit, at sites in New Mexico and South Carolina.

The organizations, Tri-Valley Communities Against a Radioactive Environment, Savannah River Site Watch, Nuclear Watch New Mexico, and Gullah/Geechee Sea Island Coalition, filed suit in late June to compel the agencies to conduct the review as required under the National Environmental Policy Act. They are now fighting an effort by DOE and NNSA to dismiss the suit over the plaintiffs’ alleged lack of standing. The groups are represented by the nonprofit South Carolina Environmental Law Project.

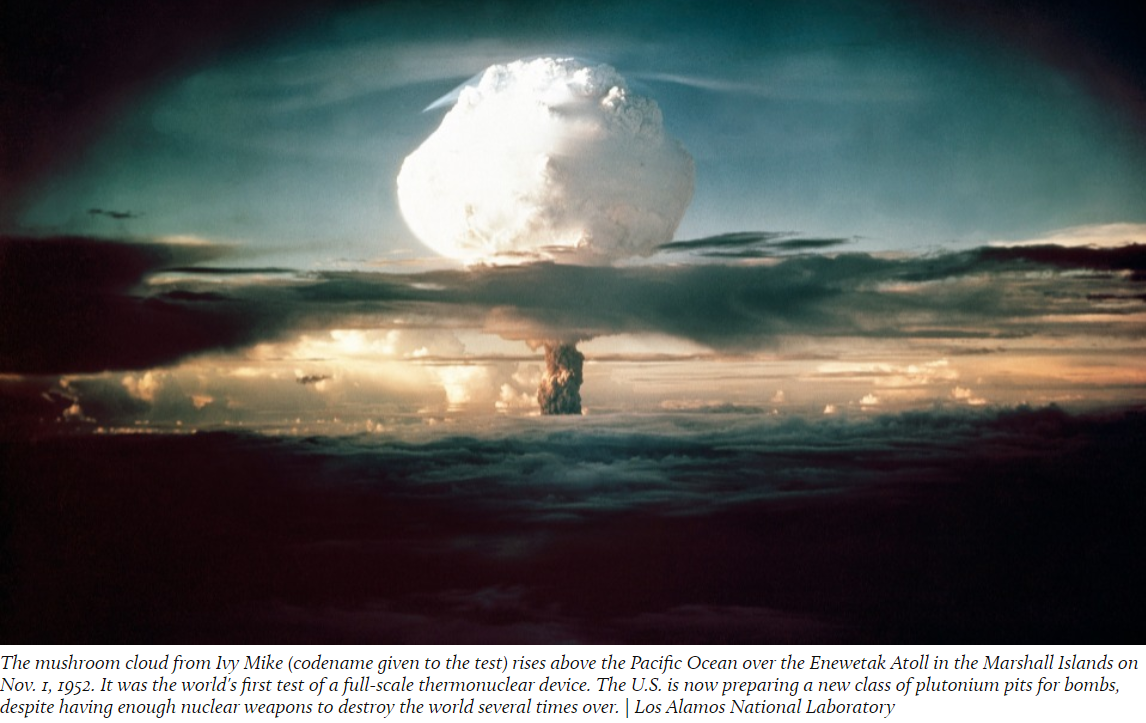

In 2018, during the Trump administration, the federal government called for producing at least 80 of the newly designed pits per year by 2030.

The public interest groups launched their suit after repeated efforts starting in 2019 to assure that DOE and NNSA would carry out their obligations to issue a thorough nationwide programmatic environmental impact statement, or PEIS, to produce the new plutonium pits at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and the Savannah River Site in South Carolina.

The public interest groups launched their suit after repeated efforts starting in 2019 to assure that DOE and NNSA would carry out their obligations to issue a thorough nationwide programmatic environmental impact statement, or PEIS, to produce the new plutonium pits at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico and the Savannah River Site in South Carolina.

The organizations said that in correspondence with NNSA in March, the agency stated that it did not plan to review pit production, relying instead on a decade-old PEIS and a separate review limited to the Savannah River Site.

Although more will be known when the Biden administration completes the Nuclear Posture Review now underway, the administration’s request for $43.2 billion in fiscal 2022 to maintain and modernize the U.S. nuclear arsenal, and individual items to expand U.S. capabilities including pit production, very much follows the Trump administration’s spending patterns. The proposed nuclear weapons spending comes to nearly 6 percent of the $753 billion the current administration is asking for national defense, itself a total marginally higher than under Trump.

The plutonium pits, built with completely new components, are first intended for the W87-1, a controversial new nuclear warhead being developed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, Calif., to go on the new Ground Based Strategic Deterrent missile which is intended to replace current ground-based ICBM missiles.

In responding to the attempt to dismiss their suit, the four organizations emphasized that DOE’s and NNSA’s pit production plan would involve extensive processing, handling, and transportation of extremely hazardous and radioactive materials, and presents a real and imminent harm to the plaintiffs and to the frontline communities around the production sites.

Queen Quet, founder of the Gullah/Geechee Sea Island Coalition, pointed out that environmental pollution at the Savannah River Site would make its way into the watershed that travels to the Atlantic coast, which environmentalists are already trying to save through resiliency planning. “So,” she said, “it is antithetical to that effort and counterproductive to seek to restore and protect one area of South Carolina while allowing an environmentally harmful project such as this to go forth in another area.”

Tom Clements, director of SRS Watch, in Columbia, S.C., said the four groups “are fighting a central and erroneous claim … that we are challenging a congressional mandate concerning the number of pits to be produced. It almost appears that Department of Justice lawyers lacked sound arguments to challenge our lawsuit and simply made up the assertion that we were challenging the number of pits to be produced, which is obviously not the case.”

Jay Coghlan, director of Nuclear Watch New Mexico, said the government needs to explain to taxpayers why it wants to spend over $50 billion on new plutonium pits when there are already thousands of existing pits with a proven shelf life of 100 years or more. The plan has “everything to do with building up a new nuclear arms race that will threaten the entire world,” he said, adding that unanalyzed impacts of pit production and associated waste disposal would also involve many other sites across the country.

Marylia Kelley, executive director of Livermore, Calif.-based Tri-Valley CAREs, said her organization has obtained government documents “disclosing that expanded pit production will introduce new plutonium dangers in my community—and the NNSA’s failure to produce a program-wide review leaves those risks unexamined and unmitigated.” Noting that her organization has proof that plutonium will travel “through multiple states to Livermore for ‘materials testing,’ Kelley said, “I’m here to say my community matters. We have a right to know what risks we are being asked to bear, and the government has no leave to ignore it.” She expressed confidence the government’s “specious claims” will be rejected.

In a telephone interview with People’s World, Kelley emphasized that the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, signed into law in 1970, is the country’s most fundamental environmental law. Under NEPA, federal agencies must assess the environmental effects of their proposed actions before they make decisions, and agencies must provide opportunities for public review and comment on their evaluations.

Because there’s been no analysis of what’s involved with plutonium being shipped from Los Alamos Lab in New Mexico to Livermore Lab, in the San Francisco Bay Area, Kelley said, “We don’t know how much plutonium, we don’t know how often it would come or for sure how it would come, and what they’d be doing with it at Livermore Lab.” She said a hint about what would happen at the lab came when she saw in the 2022 fiscal year budget request, an item for Livermore Lab to buy new plutonium glove boxes.

“If they do this analysis, the government, the agency itself, has in front of it all of the risks, environmental aspects, and potential problems,” she said. “Decision-makers in Congress have that in front of them as well—what are the risks, what are the environmental impacts and the health impacts of doing this. And the public has it in front of them, and can therefore act because they have the information on which to act.”

Among possible results: The program moves forward as currently planned—“a valiant try, and we’ve at least alerted and informed the public and decision-makers of things they didn’t know before.” The government could decide to modify the program, making significant changes in the number of pits, and how and where they are produced. Mitigation measures, which often happen after NEPA analyses, might mean the agency changes some things, to at least address some obvious risks uncovered during the analysis.

“All these options are on the table,” Kelley said. “The DOE and NNSA are, I think, trying very hard not to connect the dots between all the different parts of this program so they don’t have to address any of the actual and obvious risks it will pose to its workers and the American people.”

Some of those risks are graphically illustrated by the experiences of communities that surround Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Since LLNL was founded in 1952, its surroundings have changed dramatically. Once a very rural area, the region is now part of the metropolitan San Francisco Bay Area. Over 7 million people live within a 50-mile radius and about 100,000 live immediately adjacent to the lab.

“Livermore Lab is unique in that the main site is in the City of Livermore, and the main site is where they keep the plutonium,” Kelley said. “The main site is where the work would be done, this is where the glove boxes would go, this is where the plutonium would come.”

Kelley says past experiences may hint at what the consequences of the new plans could be:

- Both LLNL’s main site and its high explosives testing range at Site 300, near the city of Tracy, are federal Superfund clean-up sites.

- Livermore’s main aquifer has been contaminated by the lab, which is still trying to clean up an offsite contaminant plume, a body of groundwater affected by pollutants in the soil or the aquifer. Onsite, there are spikes of radioactive tritium “and a whole smorgasbord of other contaminants.”

- That “smorgasbord” is also present at Site 300, with perchlorate, uranium, and very high levels of radioactive hydrogen, or tritium.

For many years, she said, bomb blasts with radioactive materials were conducted in the open air at Site 300, to test new designs. While blasts with radiation are now conducted inside a contained facility, toxic bomb blasts are still done in the open air.

The government estimates that the cleanup will take until about 2060, Kelley said. “And at Site 300, some contamination will remain there in perpetuity—parts of Site 300 are essentially a sacrifice.” Such contamination is present at all U.S. nuclear weapons sites, “and at some of the big production sites, the contamination is even worse.”

Tri-Valley CAREs has reviewed government documents showing that over the years, Livermore Lab has released over one million curies of radiation into the atmosphere—more than the radiation estimated to have fallen on the residents of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, when the U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb on the city.

Asked how members of the public can further explore nuclear weapons issues and express their concerns, Kelley urged people to check out the websites of the organizations participating in the suit, including the South Carolina Law Project’s special section NEPA the pit production program, and to share the information as widely as possible.

For example, she said, Tri-Valley CAREs’ website tells readers how to connect with a virtual letters-to-the-editor writing party on the first Thursday of the month, and a virtual meeting for all interested members of the public on the third Thursday.

“None of this can happen without money, many tens of billions of dollars,” Kelley said. “And when you count the new warhead and delivery system, many hundreds of billions of dollars. That money comes from the Congress.

“Folks can call their member of Congress and say they don’t want this funded. If that member is on the Appropriations Committee or the Armed Services Committee, they have a special oversight role. But every member of Congress has a voice and a vote.”